Gastroparesis - Delayed stomach emptying

What is gastroparesis?

Gastroparesis is a disease or disorder of the muscles of the stomach or the nerves controlling these muscles that causes them to stop working. This results in the stomach taking too long to empty its contents into the intestine and an inadequate grinding of food.

More common in women. A hormonal link has also been suggested, as gastroparesis symptoms tend to worsen the week before menstruation, when PROGESTERONE levels are highest. Dysmotility can also affect men and children;

Gastroparesis occurs for different reasons. A study (Soykan I et al, 1998 ) of 146 patients with gastroparesis seen at a referral center over the course of 6 years demonstrated that: .

- 35% had idiopathic gastroparesis. i.e. it “came out of the blue”, and they didn’t know why!

- 30% had diabetic gastroparesis;

- 13% had gastroparesis related to surgical injury of the vagus nerve;

- 7.5% of cases were related to Parkinson’s disease or other neurologic conditions;

- 4.5% were related to intestinal pseudo-obstruction;

- Remaining 10% of cases included other miscellaneous conditions. Specifically connective tissue diseases, such as scleroderma.

Physiology of gastroparesis

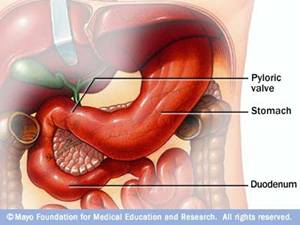

Normal Food path from stomach to small intestine. The stomach is a muscular sac about the size of a small melon, that expands when you eat or drink to hold as much as a gallon of food or liquid. The stomach mechanically churns and pulverizes your food while hydrochloric acid (HCl) and enzymes requiring an acid environment break it down. Muscle fibers of the stomach wall create structural elasticity and contractibility, both of which are needed for digestion and propelling food towards the intestines.

Pyloric Sphincter / Valve controls release of food from the stomach

- The pyloric sphincter (valve between stomach and intestines) stays closed while food is being digested in the stomach (to keep the food inside the stomach). During digestion, strong muscular contractions (peristaltic waves) push the food toward the pyloric valve, which is the gateway to the upper portion of your small intestine (duodenum);

- When HCl and the stomach enzymes have had enough time to do their job, alkaline bile (from gall bladder) and pancreatic juices (a watery bicarbonate solution) are secreted into the upper small intestine (duodenum). This prevents damage to the duodenum when the stomach’s highly acidic contents are released.

Once the duodenum has become strongly alkaline, the pyloric sphincter receives a signal to open, and the partially digested food is released into the small intestines. This is where most of the absorption of nutrients takes place.

- Chronic dehydration will prevent pyloric valve from opening. Due to dehydration, there is an insufficient water supply in the body’s circulation from which the pancreas can produce the watery bicarbonate solution required to protect intestinal lining from stomach’s acidic contents

Complications of gastroparesis

- Bacterial growth in the stomach – from fermentation of the stomach contents when it lingers too long.

- Food can harden into solid masses (called bezoars) – that may cause nausea and vomiting. Bezoars can be dangerous if they obstruct the passage of food into the small intestine.

- Can make diabetes worse – when food delayed in the stomach finally enters the small intestine and is absorbed, blood glucose levels rise. Since gastroparesis makes stomach emptying unpredictable, blood glucose levels can be erratic and difficult to control.

What are the symptoms of food sitting too long in stomach?

- Nausea, vomiting, excess belching, reflux of stomach acid and bloating – are the common symptoms of dysmotility;

- Abdominal pain;

- Some people feel full and uncomfortable – even after just a few mouthfuls of food;

- Some feel lethargic

What causes gastroparesis?

Triggered by certain foods, way of eating, infections, medications etc.

- Eating fatty /rich foods, late at night or on-the-go

- Drinking too much alcohol

- Having a viral stomach upset

- Imbalance of magnesium, calcium, potassium – these minerals are important operators in muscle function; ideally calcium intake should be twice that of magnesium, but typically in a Western diet, intake is~4 to 1 and magnesium deficiency in the body is common

- Side-effect of medication – particularly those that slow intestinal contractions, E.g. narcotic pain relievers, opiates, or antibiotics.

- As a complication of:

| • Diabetes (common cause, damages vagus nerve) | • Parkinson’s disease |

| • After stomach or vagus nerve surgery | • Hyperthyroidism |

| • Anorexia nervosa | • Paralysis |

| • Post-viral syndromes | • Smooth muscle disorders – E.g. amyloidosis, scleroderma |

Damaged vagus nerve (i.e. vagal neuropathy)

Normally, food is moved through the GI tract via contractions modulated by the vagus nerve under central nervous system control – which modifies gastric and sphincter contractility in response to feedback from:

- Stimulation after eating – causes gastric contractions to propagate through the stomach.

- Various intestinal peptides – E.g. motilin and cholecystokinin.

If damaged, the vagus nerve can send wrong or weak signals between the body and the brain – the vagus nerve can be damaged by:

- Surgery on the esophagus or stomach

- Injury or upper respiratory infections

- When blood glucose remains high for an extended time – as in diabetes and thyroid disease.

- Alcoholism – found to contribute to vagal neuropathy.

Vagal nerve neuropathy can be reversed – when possible, measures can be taken to eliminate the cause of the condition. E.g. diabetics control their blood sugar; alcoholics decrease their alcohol intake. Those recovering from severe upper respiratory infection may regain normal vagal nerve function.

Gastroparesis is usually a consequence of:

- Any disruption in the timing or strength of normally propagated gastric contractions (i.e. unsynchronized muscle contraction and relaxation / too weak / not frequent enough contractions) – and will cause food not to be propelled forward towards the small intestine for further digestion;

- Non-opening of pyloric sphincter (valve at bottom of stomach)-its contracting too strongly prevents release of food into small intestine.

How to treat gastroparesis

Using diet / nutrition

Drink plenty of water. To avoid insufficient alkalizing pancreatic juices, which would prevent pyloric valve from opening.

Assure sufficient magnesium. To ensure muscle valves operate/relax properly; can be obtained from organic whole food sources, but supplementation (orally ~600 mg /day) or transdermally (with magnesium chloride) may be necessary.

Magnesium – “The Missing Miracle Mineral”

Sensible, healthy eating is vital to reduce dysmotility

- Take time to eat and enjoy food

- Don’t drink too much alcohol

- Eat lighter, smaller meals regularly throughout the day

- Avoid identified trigger foods

- Don’t eat too much fat – which causes the release of hormones that slow down stomach emptying.

- Combining only specific food-types shortens digestion time in stomach

- DON’T eat Carbohydrates with protein

- Eat Protein with vegetables or fruit

- Eat carbohydrate with vegetables

- Try to eat fruit on its own on an empty stomach (don’t mix melons with other fruits)

Control glucose levels. High blood sugar tends to slow gastric emptying. Iodine supplementation can normalize thyroid hormone levels.

Note that cinnamon can SLOW gastric emptying. Studies of patients with type 2 diabetes have shown that cinnamon lowers fasting serum glucose, triacylglycerol, LDL and total cholesterol concentrations. However, Hlebowicz et al found that the addition of 6 g of cinnamon to rice pudding significantly delayed gastric emptying and lowered the postprandial glucose response without affecting satiety in healthy subjects. Thus, people with gastroparesis need to be mindful of cinnamon intake at daily doses of 6 g (about 2 tsp.) or higher. Hiebowicz J et al,. 2007.

Herbal Solutions

Iberogast™. In addition to gastroparesis, this synergistic herbal extract of 9 plants has been very succesfully used against non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), gastritis, and bloating. Shown effective in over 15 clinical studies, this patented herbal extract relieves gastrointestinal problem symptoms, and unlike mainstream medications, without serious side-effects:

- Accelerates gastric emptying

- Reduces pain and cramping

- Alleviates heartburn

- Relieves bloating and induces expulsion of gas from the intestines

Peppermint (Enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules). Peppermint helps relax the digestive tract’s muscles and relieve excessive gas, according to the University of Maryland Medical Center.

- Study found that peppermint oil accelerated the early phase of gastric emptying while inducing pyloric sphincter relaxation. Inamori M et al, 2007

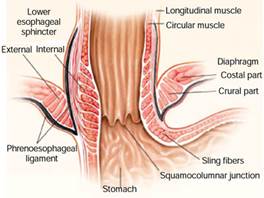

- Caution should be used in patients with known gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) – sInce peppermint oil decreases lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure;

- Enteric-coated peppermint oil capsules deliver oil directly to the intestines – instead of being absorbed into the blood stream from the stomach

- IBS dose is 0.6 ml per day -can be used concurrently with Iberogast™

- Peppermint oil is sometimes combined with rosemary and thyme oils -for IBS treatment

Ginger root. Reported to improve upper GI symptoms. Also studied for postoperative nausea, morning sickness, and chemotherapy-induced nausea. Ernst E, Pittler MH, 2000

Ginger has also been shown to accelerate gastric emptying and stimulate antral contractions in healthy volunteers.

- Wu et al demonstrated that ginger (1,200 mg / ~½ tsp. daily) accelerated gastric emptying and stimulated antral contractions in healthy volunteers. These investigators reported that gastric antral area decreased more rapidly (P<.001) and the gastric half-emptying time was less after ginger ingestion than after placebo ingestion, whereas the frequency of antral contractions was greater. Thus, ginger may promote gastric antral contractions and promote gastric emptying at a daily dose of 1,200 mg. Wu KL et al, 2008

Drugs / Other

Prokinetics. Medicines that stimulate stomach contractions. Thus promote the emptying of the stomach. E.g. Metoclopramide lowers the pressure threshold in the stomach that triggers the process of peristalsis (coordinated, rhythmic muscle contractions that help move food through the GI tract). It also boosts both strength and frequency of muscle contractions, and relaxes the pyloric sphincter. However, prokinetics provide only short-term relief and have serious side effects limiting their use:

- Metoclopramide is associated with depression and severe muscle twitching;

- Bethanecol may cause dizziness or lightheadedness;

- Cisapride has been linked to fatal heart arrhythmias.

Botulinum toxin. Used in very small doses to improve symptoms of gastroparesis in some patients to treat muscle spasms; decreases muscle activity by blocking the release of ACETYLCHOLINE hormone;

References

Ernst E, Pittler MH, Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000; 84:367-371 PubMed

Hlebowicz J, Darwiche G, Bjãrgell O,Almér LO. Effect of cinnamon on postprandial blood glucose, gastric emptying, and satiety in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1552-1556. PubMed

M, Akiyama T, AkimotoK, et al. Early effects of peppermint oil on gastric emptying: a crossover study using a continuous real-time 13C breath test (BreathID system). J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:539542. PubMed

Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, et al. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastro paresis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2398-2404.

Wu KL, RaynerCK, Chuah SK, et al. Effects of ginger on gastric emptying and motility in healthy humans. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20436440 PubMed